Note: The portraits in this series, while representational, are not exact likenesses of the real-life individuals whose stories are shared. All individuals featured here are deceased, gone public with their stories, or have left the U.S with no plans to return.

The line between documented and undocumented visitors and immigrants is thinner than many people imagine. Some previously documented people do not even know they have become undocumented, given the complexities of the immigration system and the huge paperwork backlog. What is your mental picture of an undocumented individual that is subject to detention and deportation? What do you think their experience is? Where did you get this narrative from? Does the first story that come to your mind match any of the stories below?

Content note: mention of incarceration and deportation

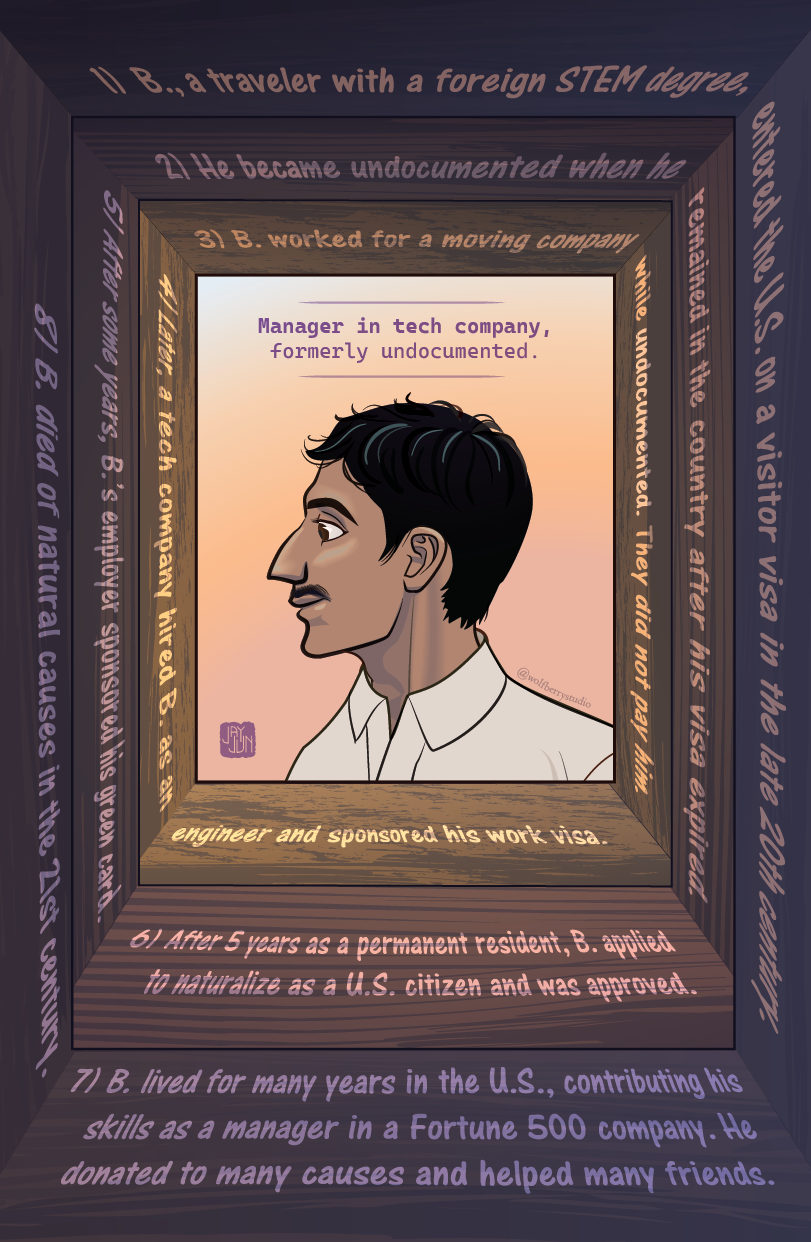

Manager in tech company, formerly undocumented

B., a traveler with a foreign STEM degree, entered the U.S. on a visitor visa in the 1990s. He became undocumented when he remained in the country after his visa expired.

B. worked for a moving company while undocumented. They did not pay him.

Later, a tech company hired B. as an engineer and sponsored his work visa. After some years, B.’s employer sponsored his adjustment of status from work visa holder to green card holder (U.S. permanent resident).

After 5 years as a permanent resident, B. naturalized as a citizen of the U.S. The formerly undocumented B. lived for a few more decades in the U.S., contributing his engineering skills by working as a midlevel manager in a Fortune 500 company. He donated to causes and helped many friends. B. died of natural causes in the 21st c.

U.S.-educated engineer detained and deported

C., an international student accepted to a master’s program at a U.S. university, entered the country on a student visa in the mid-2010s.

Upon graduating with an engineering degree, C. applied for and received work authorization under the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program that allows foreign students who have graduated from U.S. universities to gain work experience related to their major. She was hired by a Fortune 500 company in the U.S.

C.’s employer sponsored her work visa application because they wanted her to continue working for them after the future expiration of her student visa.

But due to the unusually long visa processing time resulting from policy changes starting in 2017, C.’s student work authorization documentation expired before her new work visa was approved. She did not realize that she was now undocumented.

Without warning, immigration agents came to the engineer’s home and took her into custody. Rather than remain in detention indefinitely, C. begged to be deported to her home country right away. But that did not happen. She had to wait to see an immigration judge who could order her deportation, and there was a backlog of deportation cases waiting to be heard.

C. was in immigration detention for more than 2 weeks before she was allowed to return to her home country. The first plane ticket that her U.S.-based cousin purchased for her departure was rejected by immigration authorities because it involved a stopover within the U.S.

Disgusted by her treatment, C. returned to her country of origin, vowing never to return to the U.S.

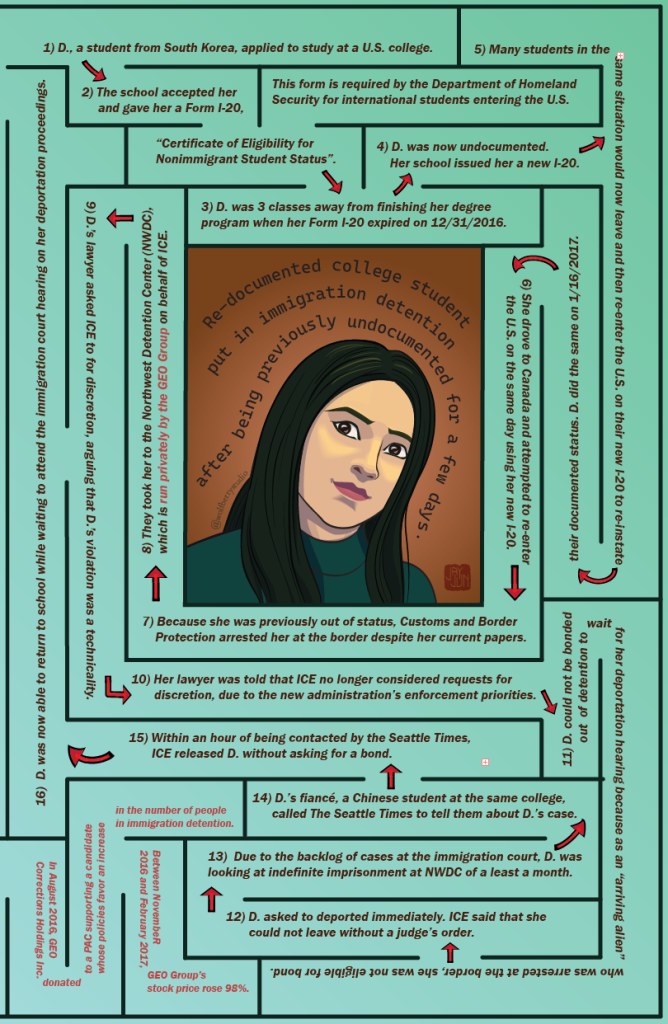

According to a January 2017 Consumer Affairs report Private prison industry sees big leap in stock price … , In August 2016, GEO Group subsidiary GEO Corrections Holdings Inc. contributed more than $225,000 to a PAC supporting a candidate whose policies favor an increase in the prison population, including the number of people in immigration detention.

Between November 2016 and February 2017, the stock prices of the two biggest private prison operators – CoreCivic and Geo Group – practically doubled. CoreCivic (CXW) stock was up 140% and Geo Group (GEO) stock rose 98%(Source: Private prison stocks up 100% since …, CNN Business, February 24, 2017)

Re-documented college student put in immigration detention

after being previously undocumented for a few days

D., a student from South Korea, applied to study in a U.S. college. When the school accepted her, it gave her a Form I-20, “Certificate of Eligibility for Nonimmigrant Student Status”, required by the Department of Homeland Security for international students entering the U.S.

D. was 3 classes away from finishing her degree program when her Form I-20 expired on 12/31/2016. D. was now undocumented. The school issued her a new I-20.

Many students in a similar situation would then leave the U.S. and re-enter on their new I-20 to re-instate their documented status. D. did the same on 1/16/2017. She drove to Canada and attempted to re-enter the U.S. a few hours later using her new, valid document.

Because she was previously out of status, Customs and Border Protection arrested her at the border and took her to the Northwest Detention Center (NWDC) run privately by the GEO Group on behalf of ICE.

D.’s lawyer called ICE to ask for discretion, arguing that her student’s violation was a technicality. The lawyer was told that ICE no longer considered requests for discretion due to the new administration’s enforcement priorities. D. could not be granted bond to leave detention to wait for her deportation hearing because as an “arriving alien” who was arrested at the border, she was not eligible for bond. D. asked to be deported to South Korea immediately rather than fight her deportation case. ICE said that they could not send her back until a judge ordered it.

Due to the backlog of cases at the immigration court, D. was looking at an indefinite stay at NWDC. Her lawyer believed she would be jailed for at least a month. At this news, D.’s fiancé, a Chinese international student at the same college, called Seattle Times about D.’s case. Within an hour of being contacted by the Seattle Times, ICE released D. without asking for a bond. D. was now able to return to class while waiting for the immigration court hearing on her deportation proceedings.

Notes: (CW: mention of violence suicide in paragraphs below)

D.’s story can be found in the Tacoma News Tribune under the title “Paperwork tangle nets visiting Korean student a 2-week stay at Northwest Detention Center.”

Northwest Detention Center (NWDC) in Tacoma has been the site of many hunger strikes by immigration detainees protesting harsh conditions. There were at least 13 hunger strikes in 2024 alone. (Source: Immigrants Begin 13th Hunger Strike This Year at Tacoma Detention Center, People’s Tribune, 7 Dec 2024)

In 2018, Mergensana Amar, an asylum seeker, died after a suicide attempt at NWDC, 11 months after he sought asylum at the US border in 2017. (Source: What happened to Mergensana Amar? The Russian immigrant’s handwritten note raises questions about treatment at Northwest Detention Center, The Seattle Times, 30 Nov 2018)

Too often we turn a blind eye to the issues facing people from demographic groups that we don’t identify with. We may even blame them for their misfortune, assuming that the same cannot happen to us. But an increasing number of people, including US citizens and legal permanent residents, have been subjected to arbitrary arrest and unnecessarily lengthy detentions. People who look like us, people who could be our relatives, have disappeared into an opaque, unaccountable system. All of us benefit from efforts to uphold due process rights.